Steve Reddy Liverpool Domestic Abuse Strategic Lead and mother-in-law jokes about women’s suspicious deaths

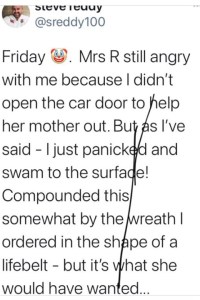

Steve Reddy, Director of Liverpool City Council Children & Young People Services and Domestic Abuse Strategic Lead tweeted the following ‘joke’:

“Friday [clown face emoji]. Mrs R still angry with me because I didn’t open the car door to help her mother out. But as I’ve said – I just panicked and swam to the surface! Compounded this somewhat by the wreath I ordered in the shape of a lifebelt – but it’s what she would have wanted…” (9 April 2021)

Angela Clarke, on twitter Angela Madigan, Liverpool City Council Domestic Abuse and Domestic Homicide Review Commissioner doesn’t seem to think so, if her response: “Back with a vengeance“ is anything to go by. And to which Reddy ‘oh-so-humorously’ responded “Cheers mate, I did it again.”

Liverpool’s independent specialist domestic abuse service, (LDAS), didn’t share the amusement and asked the Chair of the domestic abuse strategy group why he was using Bernard Manning humour about women dying.

After trying to justify himself, Reddy replaced the subject of his joke with his father-in-law, before also deleting this second version, shortly after he said that he apologised unreservedly for any offence caused, it was absolutely not his intention.

Mother-in-law jokes are or were a misogynistic trope of the UK mainstream cultural fabric. They position younger men as normative and socially valuable, whilst positioning older women as the antithesis to this, disdainful and other, whilst reminding younger women of their destiny as disposable objects of ridicule with patriarchal best-before dates and signalling to younger heterosexual men that they should be wary of what their female partner may become. As LDAS pointed out, mother-in-law jokes belong in the dustbin of entertainment from the 1970s when sexist, racist humour was a lazy prop for sexist racist comedians like Manning. But the stereotype endures.

The Femicide Census found that 13 women in the UK had been killed by the partner or ex-partner of their daughter between 2009 and 2018, (in other words, 13 men killed women who were or had been their mother-in-law or equivalent), just over one percent of all women killed by men in the UK. More extreme than mother-in-law jokes, certainly, but not unconnected. Societal norms and values can either create a conducive context for men’s violence against women or they can challenge and deconstruct. Mother-in-law jokes in particular and the normalisation of men’s violence against women and the perceived different social value of women and men (sex inequality) are the backdrop of these men’s murderous intent and actions.

Between 2009 and 2018, 43 women in Merseyside were killed by men. They include 28-year-old Jade Hales and her mum, Karen Hales, 53, making Karen one of the 13 women who were mother-in-laws noted above. In 2016, Anthony Showers, 42, broke into his ex-partner Jade’s home and killed and raped her and killed her mother, his ex-mother-in-law, Karen, who was disabled and needed a frame to walk, by bludgeoning both women to death with a hammer. This year, Merseyside MPs held an emergency meeting called by Labour MP Paula Barker, after three women, Helen Joy, Rose Marie Tinton and N’Taya Elliott Cleverley, were killed in one weekend in January. Surely, this alone should mean that Liverpool’s senior council officials recognised – for themselves – that women’s suspicious deaths were not an appropriate subject matter for humour. It is inconceivable that the person who commissions domestic homicide reviews in the city was unaware of this.

Merseyside police reported an increase in reports of domestic abuse of 10.4 per cent – equivalent to 18,782 victims – between April 1 and November 30 2020, compared to the same period the year before.Yvonne Roberts, writing for the Observer, reported that in the last year LDAS, Liverpool’s specialist independent service for women, has seen a 145% increase in demand for counselling and group-based support and the highest number of self-referrals in its 15-year history. Yet this specialist independent service of experts has increasingly found themselves frozen out by Liverpool City Council and council funded services for women victims of domestic violence and abuse in the city are provided by a national provider that does not have a specific focus on women victims of men’s violence. YSadly this commissioning pattern, ignoring decades of research that show that women victim-survivors of men’s violence are best served and feel safer using specialist independent local women-led services and moreover, ignoring that women are the vast majority of victims of domestic and sexual violence, has been seen across the UK for more than a decade. If a woman in Liverpool looks for domestic abuse support on Liverpool City Council’s website, the first ‘service’ she will see is that for ‘Ask Ani’, a national scheme much vaunted by the government, whereby women can approach any one of 2,500 pharmacies and ask for Ani. In contrast to the experience of Liverpool’s specialist service and those of specialist independent women’s charities across the country, the Ask Ani scheme, with its 2,500 access points, has attracted less that one woman a week across the entire country since its launch in January. Women who are subjected to men’s violence reach out to those they trust. It doesn’t look to me like Ask Ani is it. When abused women don’t access services, it doesn’t mean that abuse isn’t happening, it’s much more likely to mean that (if they know about the service) they don’t think it can or will help.

Men’s fatal violence against women isn’t the only reason that Liverpool has made the national news this year. Girls at Broughton Hall Catholic High School, in West Derby, Liverpool, were advised to wear shorts under their skirts after male pupils were allegedly caught taking photos up their skirts as they used a transparent glass staircase. The school had previously taken swift action to address its concerns that females were wearing inappropriate pencil skirts by sending them home. Evidently the school expects females to take responsibility for the male gaze and sexual harassment.

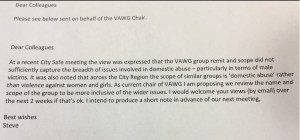

Steve Reddy, Director of Liverpool City Council Children & Young People Services and Domestic Abuse Strategic Lead, also has form with his regard to his antipathy to recognising the critical importance of sex differences with regards to sexual and domestic violence and abuse. In 2018, Steve Reddy’s first act, as Violence Against Women and Girls (VAWG) Strategy Lead was to propose that the VAWG strategic group was renamed because (to quote from his own email) the “remit and scope did not sufficiently capture the breadth of issues involved in domestic abuse – particularly in terms of male victims.”

The United Nations recognises that (men’s) violence against women in public and private life impedes the ability of women and girls to claim, realize [SIC] and enjoy their human rights on an equal foot with men. Is it enough if someone in a position of responsibility apologises for an offensive joke? One of the things I’d want to know is whether ‘the joke’ chimes or contrasts with their track record. We can all say or do things that we regret and don’t really mean when we reflect on them later. But it’s not the only question. What if that person has a lead role with regards to the protection of the demographic that is the subject of said joke? What if violence – including fatal violence – against that demographic has reached unprecedented levels? What if that person’s track record is one of undermining the human rights abuses of and specialist provision for that subjugated demographic? Then, no, whether causing offence was the intention or not, I don’t think it is good enough.